In the highly populated Denver metropolitan area, Centennial Airport applies IP-based capture and streaming technologies to minimize regional noise impact – to the benefit of community relations.

The Denver-Aurora-Lakewood Colorado metropolitan statistical area comprises 10 counties with a population exceeding 2.8 million. The population continues to be among the fastest growing nationwide; in 2014, the United States Census Bureau confirmed the region experienced the second largest population growth over the previous 12 months, reporting a 2.4 percent boost.

The continued population growth means that the two largest regional airports, Denver International Airport (DEN) and Centennial Airport (APA), are especially sensitive to how aircraft-related noise impacts neighbors. In addition to continuous expansion of existing residential areas, the consistent population growth drives construction of new neighborhoods.

Easily assembled, Centennial Airport’s portable noise monitoring system can be on site and online, delivering data to the system within 30 minutes.

As with all airports nationally, the FAA provides flight data and other information to DEN and APA to help them understand how flight paths and aircraft contribute to regional noise impact. The FAA’s goal, partially based on a 2013 noise reduction standard from the International Civil Aviation Organization’s Committee on Aviation Environmental Protection, is to limit the number of residents exposed to Day Night Average Sound Levels, or DNLs. A 65 db level is widely considered the DNL threshold for “significant noise,” and is the level that airports aim not to exceed.

While the 2013 standard and similar initiatives have been instrumental in reducing noise through new aircraft technology development, fleet transitions and other programs, airports are still, for the most part, required to monitor noise and understand the impact on neighboring residential areas. Some have very stringent regulations and requirements to meet; others, like APA, simply monitor for scientific purposes and/or aim to reduce noise as a neighborly gesture.

However, management of noise monitoring systems and associated data collection has long been a tedious process. Integration and ongoing maintenance of remote noise monitoring terminals has long equated to substantial time and labor investments, and delivering noise information back to control centers has been tedious at best. However, migration to IP networks, audio streaming and managed services – or SaaS applications – have helped airports like APA discover new operational efficiencies and reduce costs.

Efficient Technology

Denver International Airport, which declined to be interviewed for this story, is considered the fifth busiest airport in the United States, with claims of serving more than 53 million passengers annually. The airport works in accordance with the local Adams County government to minimize noise exceedances.

Across the city, Centennial Airport applies an aggressive noise monitoring operations, but for very different reasons.

“Centennial Airport has no scheduled airline traffic,” said Deborah Grigsby Smith, public information officer. “We are general aviation only.”

Portable noise monitoring systems, like this one used by Centennial Airport staff members Mike Fronapfel, left, and Aaron, right, help apply hard data to noise events to more accurately Identify trends and anomalies.

However, that doesn’t mean APA lacks activity. With more than 300,000 operations annually, APA ranks among the busiest general aviation business airports in the United States. It is also an important revenue source for the local economy, generating approximately $1.4 billion in economic impact, each year.

APA is not subject to airport traffic limitations since it is located outside of the city of Denver, and is not party to any specific governmental agreements to minimize noise. However, the Arapahoe Country Public Airport Authority, which owns and operates APA, has proactively completed the “Centennial Airport Part 150 Noise Compatibility Program,” based on a voluntary FAA program that recommends guidelines for airport noise compatibility planning.

APA is in the process of updating its Noise Exposure Map, which provides a current baseline, as well as a five-year forecast, of aircraft noise exposure levels based on existing and future traffic, respectively. To support these efforts, the APA noise monitoring team relies on a Bruel & Kjaer Noise Monitoring Terminals (NMTs) with integrated Barix Audio over IP devices for streaming.

“We have 12 permanent sites, half of which are solar-powered and two of which are located on airport grounds,” says Aaron Repp, noise and environmental specialist, Centennial Airport. “Between the 12 airport monitors, we have a capture rate of about 93 percent. Those monitors are placed in noise sensitive areas throughout the community, and on the approach and departing paths of the aircraft. We additionally have two portable monitors that we move between residences, construction sites and other sensitive areas to give current and future homeowners a better grasp of flight activity and related noise.”

The flexibility of the portable units has proven valuable for studying residential complaints. Repp points to one example where a resident was logging about 1,000 noise complaints per month.

“We put a monitor there for just over a week, and it really captured proof of what was happening at the residence,” he said. “We didn’t find a very high noise exposure level for that general area, but it allowed us to verify, with hard data, what was happening, and compare the community noise versus aircraft noise. In that location, the community noise was, in fact, much higher than the aircraft DNL average.”

APA applies the DNL threshold of 65 db to its noise monitoring efforts, and uses that figure within a formula to measure noise exposure averages over a one-year period.

“It’s what we, in aviation, call a logarithmic average,” says Michael Fronapfel, director of planning and development, Centennial Airport. “The noise is averaged throughout the day, and from 10 p.m. to 7 a.m., an additional 10 db is added to every noise measurement. This is because the ambient noise is usually lower at night, which makes the perceived aircraft noise much higher. That is the only federal guideline we have under the control and jurisdiction of the FAA.”

Following a study that recommended APA purchase a noise monitoring system – and a federal grant to support that purchase – APA began evaluating systems on the market. Fronapfel notes that there was only one other system in the running that is also considered very reputable, but the Bruel & Kjaer offered a bit more at the time of the purchase, including a subscription-based SaaS option that outsourced hosting and maintenance.

APA’s system came with integrated Barix devices to stream audio to APA’s control center, which eliminated more of the heavy lifting upfront. Supplied through US distributor and IP audio streaming specialist LineQ, the Barix devices can provide live audio streams, though APA rarely monitors those. Instead, they rely on Barix’s ability to reliably encode and deliver streams, which are recorded and later reviewed on a case by case basis.

“For our purposes, we don’t need live streaming to verify noise exposure at the site,” says Fronapfel. “Instead, the live audio is captured from the NMT microphone, and the Barix Instreamer streams that audio to a server that records the event. Our system already differentiates whether an exceedance was caused by an aircraft or community event – usually based on the length of the event, since community disturbances are typically longer-lasting. However, the recordings are useful to pull up either if additional confirmation is needed, or if there is an unusually loud aircraft disturbance we want to study, such as a military flight.”

APA’s use of noise monitoring technology proves how useful and important such initiatives can be for community relations. Before installing the system, the APA team would typically call DEN for assistance in looking up flight paths and correlating noise complaints with aircraft. Now, it can respond quickly to complaints and proactively assist the community.

For example, Repp is tasked with providing noise data and referrals to developers, as well as localized information for potential homebuyers looking to reside near the airport and surrounding areas. The system allows him to speak specifically to the site, using hard data to provide insight on flight routes and expected noise exposure; and to provide recommendations or opposition to a project based on whether it’s zoned for commercial, industrial or residential use.

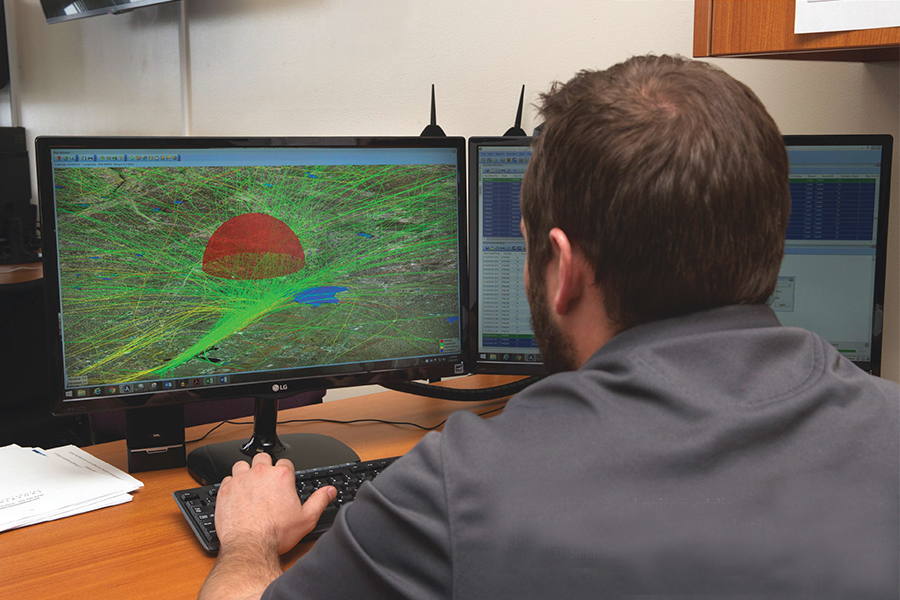

“Recently we were contacted by someone interested in buying a home near the airport, and I was able to build an imaginary cylinder, a half-mile wide by 5,000 feet tall, over the identified property, using the track filter,” says Repp. “I was able to count how many noise events happened within this cylinder. Additionally, we can trend that data and show increases or decreases over the past couple of years, speak pretty accurately to potential developers and buyers.”

Fronapfel concurs. “When we talk to planning commissions and city councils, we can support our case with hard facts and numbers based on the Bruel & Kjaer and Barix technology, whereas before they had to just take our word for it,” he says. “We can now very effectively strike the balance between the needs of APA and the noise exposure we have on residents and commercial entities. This technology has been very important to our relationship with the community.”

The continued population growth means that the two largest regional airports, Denver International Airport (DEN) and Centennial Airport (APA), are especially sensitive to how aircraft-related noise impacts neighbors. In addition to continuous expansion of existing residential areas, the consistent population growth drives construction of new neighborhoods.